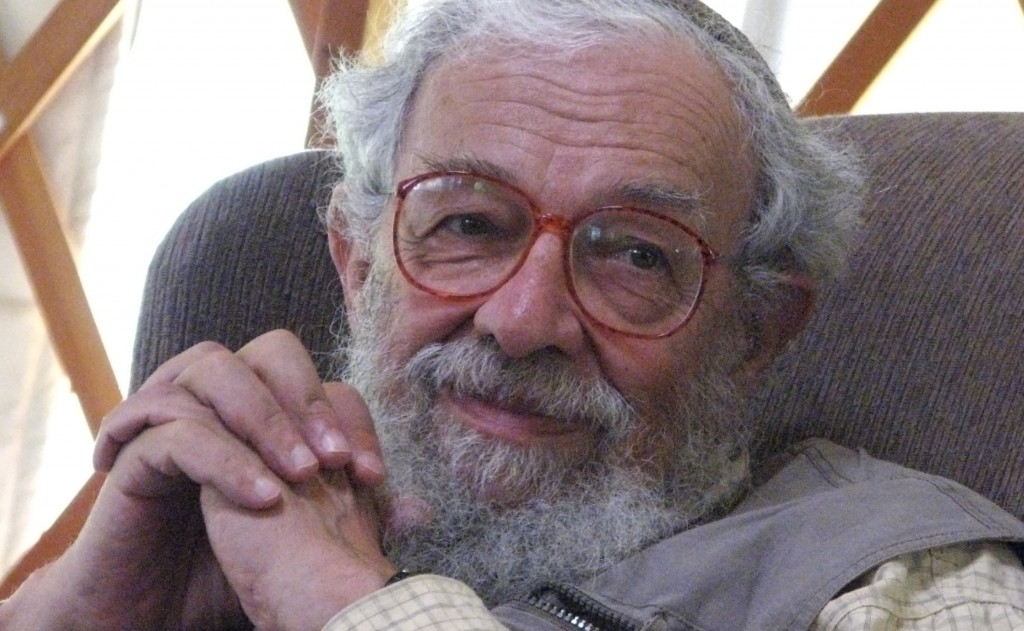

Rabbi Zalman - Founder of the Worldwide Jewish Renewal Movement (1924 - 2014)

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi first came to Winnipeg, Canada in 1956 as an ultra-orthodox emissary for the Hassidic Chabad Lubavitch movement. By the time he left the city in 1975, he had parted ways with Chabad, gained the moniker of "hippie rabbi" and had tried and tested many of the ideas that evolved into the Jewish Renewal movement.

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi — “Reb Zalman” as he preferred to be known — was the most influential Jewish change-maker of his generation. His ideas and work spawned the worldwide Jewish Renewal movement, the Havurah movement, numerous Jewish retreat centers and innovative social-change programs, and the interfaith eldering wisdom movement.

Countless innovations in Jewish life and worship throughout the Jewish denominations sprang from his creative mind and from the thought-leaders he attracted. He was visionary in creating fully inclusive community, making Jewish mysticism and joyful observance available to several generations of American Jews, as well as engaging in deep ecumenical relationships with leaders of the world’s religions.

Schachter-Shalomi’s insatiable curiosity, keen intelligence, unusual creativity, and personal courage were hallmarks of his life from a young age. Growing up in Vienna, he partook of numerous Jewish movements flourishing at the time — secular, Zionist, intellectual — well beyond his family’s Belzer Hassidic roots. Fleeing the Nazi onslaught, the family eventually made their way to New York in 1941. There, he studied to become an Orthodox rabbi and was ordained by the Lubavitch Hassidic (Chabad) yeshiva in 1947. The sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, made him an emissary to college campuses; however, he left his position after discovering a wider spiritual world and experimenting with the sacramental uses of hallucinogens.

Crossing traditional boundaries, Reb Zalman earned an MA in the psychology of religion from Boston University and a doctorate from the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College. His major academic work, Spiritual Intimacy: A Study of Counseling in Hasidism (1991), was based on his doctoral research into the system of spiritual direction practiced in Chabad. As a spiritual counselor himself, he was known for being so fully present to the other that they felt “as if no one else existed to him in that moment.” After turning 60, he also pioneered the practice of "spiritual eldering," working with fellow seniors on coming to spiritual terms with aging and becoming mentors for younger adults, as described in his book From Age-ing to Sage-ing® (written with Ronald Miller, 1995).

Simcha Raphael reading from the Torah, with Reb Zalman. Ben Lomand, CA, 1979

Drawn to the spiritual and social change movements of the 1960s, and influenced by Christian, Sufi and Eastern mysticism, he reached out to the “Baby Boom” generation of Jews hungry for spirituality. Reb Zalman is widely considered the “Zaide” (grandfather) of the Havurah movement throughout North America. In 1968, he supported Rabbi Arthur Green in the founding of Havurat Shalom in Somerville, MA, an experimental rabbinical yeshiva that grew into a collective egalitarian spiritual community. The First Jewish Catalog, written by Havurat Shalom members Richard Siegel, Michael Strassfeld and Sharon Strassfeld (1973), helped popularize Reb Zalman’s eclectic, do-it-yourself, meaning-making approach to Jewish practice.

In 1978, he founded B’nai Or (“Sons of Light” in Hebrew), a name he took from the Dead Sea Scrolls, as both a local Philadelphia Jewish Renewal congregation and a national organization. The widely worn rainbow prayer shawl he designed according to kabbalistic principles is still known as the "B'nai Or Tallit." Both the congregation and the organization later changed their names to the more gender-neutral P'nai Or ("Faces of Light"). In 1993, the national P’nai Or organization merged with Arthur Waskow’s Shalom Center, to form ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal, integrating the two principles of Tikkun haLev (repair of the heart) and Tikkun Olam (“repairing the world”).

Reb Zalman was also committed to interfaith deep ecumenism. He explored “spiritual technologies” and sustained friendships with many significant leaders, including Ram Dass, Fr. Matthew Fox, Fr. Thomas Keating, Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, Br. Thomas Merton, Br. David Steindl-Rast, and Ken Wilbur, among others. Where others saw walls, he saw doors.

In 1990, Schachter-Shalomi was among the diverse group of Jewish leaders who traveled together to Dharamsala, India, at the request of the Dalai Lama, to discuss with him how a people can survive in diaspora. That meeting of East and West was chronicled in Rodger Kamenetz’s The Jew in the Lotus, and inspired the flowering of Jewish approaches to meditation.

Schachter-Shalomi held academic posts at the University of Manitoba (Winnipeg) and Temple University (Philadelphia), and in his later years held the World Wisdom Chair at Naropa University (Boulder). He also served on the faculty of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, Omega, and many other major institutions.

Reb Zalman’s influence has widened through the work of his lay and rabbinical students. In 1974, he ordained his first rabbi, Daniel Siegel of British Columbia. After numerous private ordinations, he founded ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal’s Ordination Program, which has ordained over 80 rabbis, cantors and rabbinic pastors and provides post-graduate training as a Mashpia Ruchani (Spiritual Director). Renewal-oriented rabbis, cantors and rabbinic pastors from all seminaries now enjoy the benefits of Ohalah, a trans-denominational professional organization incubated at ALEPH.

Reb Zalman in Canada

Excerpts from My Life in Jewish Renewal: A Memoir, by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi with Edward Hoffman. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers (2012)

“In the summer of 1956, I arrived at the University of Manitoba to serve as Hillel director in Canada’s prairie heartland and begin my new position as a part-time faculty member in the Department of Judaic Studies [at University of Manitoba]. Manitoba had a well-established and vibrant Jewish community for its small size of twenty thousand souls. In 1883, [Winnipeg’s] first synagogue was built, and as early as 1921, an impressive Lubavitcher shul was opened on Magnus Street. Eventually, I came to serve as its rabbi, on top of my various teaching responsibilities….though the position carried no salary except for officiating at High Holy Day services. By the early to mid-1960s, I had become well-known throughout Lubavitch circles as “the guy who can work with far-out people” drawn to the Hasidic world.

When I arrived, my first task was to whip up enthusiasm among Jewish students. Fortunately, I never lacked for energy or ideas. I created lunch-hour programs and then weekend events in which I led retreats with students. Before long, I also founded my first Jewish meditation group. My goal was to introduce students to various Hasidic methods of meditation, inner exploration and awareness. I would also show students how to sing a Hasidic melody – and that’s when I wrote words to niggunim, so the songs would also offer content for conscious reflection.

By the time 1975 came around, I had been wishing for quite a while to be able to move to a city where my work of Jewish Renewal would be able to grow. Much of what I wanted to do for what became Jewish Renewal began with my move to Philadelphia [that year]. However, the seeds of what grew in Philadelphia were planted during my time in Winnipeg.”

Schachter-Shalomi produced a large body of written, audio and video works, typified by a breadth of knowledge, free-association homiletic style, use of psychological terminology, and imaginative metaphors from nature, science and emerging technologies. Some of his most important books include: Paradigm Shift (1993), From Age-ing to Sage-ing® (1995), Jewish with Feeling: A Guide to Meaningful Jewish Practice (2005), A Heart Afire: Stories and Teachings of the Early Hasidic Masters (2009), and Gate to the Heart: A Manual of Contemplative Jewish Practice (2013). As befits an early adopter of emerging technologies, many of Reb Zalman’s teachings are available on youtube.com.

In 2012 his book Davening: A Guide to Meaningful Jewish Prayer won the National Jewish Book Award in Contemporary Jewish Life and Practice. The last book printed before his death is the recently released Psalms in a Translation for Praying (2014), which reflects his egalitarian, post-triumphalist, ecumenical, and Gaian approach to spirituality.

In 2005, the Yesod Foundation created The Reb Zalman Legacy Project “to preserve, develop and disseminate” his teachings, which led to the 2011 donation of the Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi Collection to the University of Colorado at Boulder, and the 2013 creation, with the Program in Jewish Studies, of the Post-Holocaust American Judaism Archives.

Reb Zalman's Rooftop Encounter with Rufus Goodstriker in Calgary, Alberta By Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, from Jewish With Feeling, pp. 131 -134.

I once went to an interfaith gathering of mystics and philosophers in Calgary. We stayed in a generic modern hotel downtown and were scheduled to begin our meetings at breakfast. I got up before dawn to daven [pray], but the hotel room didn’t feel like the right ambience, so I went upstairs and found a trapdoor that led out to the roof. I stepped out, surrounded by chimneys and vents, found a corner, took out my tallis and tefillin and siddur and prepared myself for prayer.

Five minutes later, the trapdoor opened again, and up came Brother Rufus Goodstriker, a Blood Indian. We nodded to each other. Brother Rufus found his own corner, unpacked his prayer blanket, lit a little fire, and offered up some herbs. So we said our prayers, he in his corner, me in mine. The sun was rising over the prairie to the east, the alpenglow was lighting up the rocky Mountains to the west.

Just as the sun came over the horizon, Brother Rufus blew an eagle bone whistle in all four directions to greet it. Since it was shortly before the High Holy Days, I took out my ram’s horn and gave a blow, too, as is the Jewish custom.

After we had finished, Brother Rufus came over to me. “May I see your instruments?” he asked. “I wasn’t home,” he added, “so I couldn’t take a sweat, but I took a shower instead.” If I’m going to touch someone else’s spiritual instruments, he was saying, I should be ritually clean.

He picked up my tefillin first. “Rawhide,” he noted. He noticed they were sewn together with natural gut and nodded. He looked carefully at the knots and ran his fingers over them slowly. “Noble knots,” he said. Next he shook the tefillin’s headpiece and heard something move. “What’s inside the black box?” A piece of parchment, I told him, on which was written holy texts with God’s name. He nodded.

He picked up the shofar and looked it over. “Ram’s horn,” he said, blew a few loud notes, and handed it back. “Much better than cow.”

Then he examined the knotted fringes at the corners of my tallis, each with five double knots interspersed with columns of wound thread.

Brother Rufus…had examined my ritual objects with the same reverence and respect that we might reserve for, say, Native American prayer objects. He understood that these are not just mumbo jumbo from a distant past. They have meaning and power to this very day – if we let them.